El Caminito del Rey

A marvel 105 metres above the ground

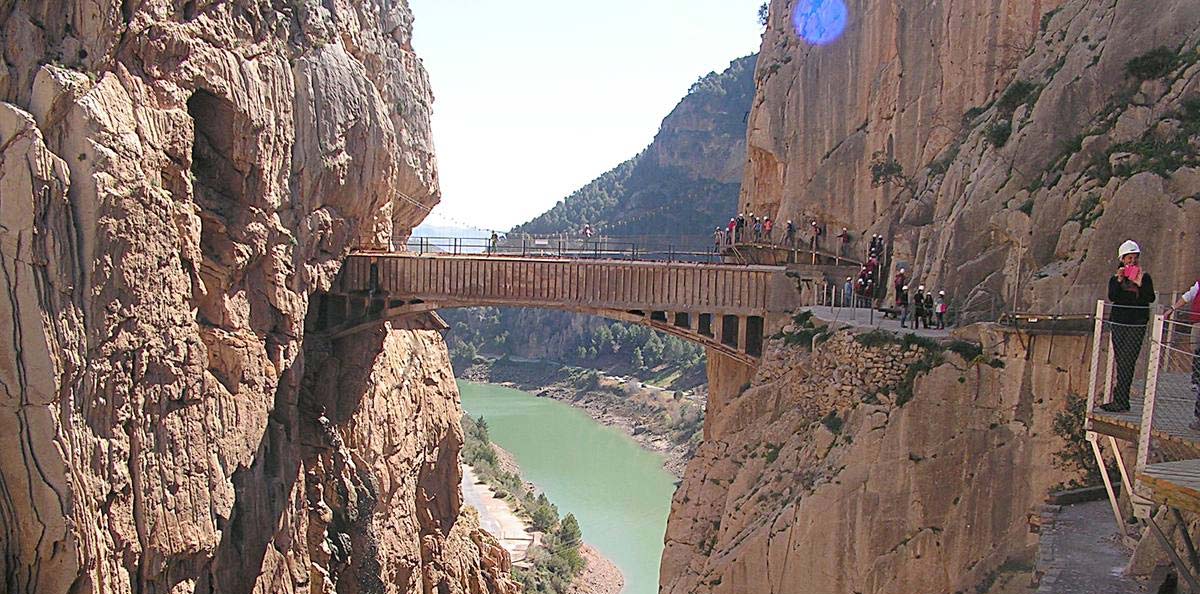

The click of the helmet being done up is like a green traffic light. There is no going back now. Ahead lie eight kilometres of walking what was once known as ‘the most dangerous walkway in the world’, but this is another Caminito del Rey, the one made of wood; a structure which passes above the original one. The climb up from El Chorro is hard and unexpected. After a short while, the ramps become steps and the vertical wall already seems overwhelming. Caution is at its peak when you step onto the first plank of the walkway, but although to the left there is empty space – with only a fence for protection – there is a strong sense of safety. You step out firmly and your camera shutter works overtime, faced with a landscape of so much beauty. On one side is the start of the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes gorge and, on the other, the blue water of the reservoir.

Suddenly, a bridge that nobody understands has appeared. 105 metres high, over empty space which can be seen below your feet. And vertigo. A great deal of vertigo. In the air float ‘water butterflies’, as local people call these drops that fall into the space and capture the light. A 34 metre-long bridge hangs from one side to the other. You try to cross it quickly, to leave it behind without looking at anything. More vertigo. “You have to enjoy the bridge,” someone says.

There is no danger, but you feel brave, as if you were doing something truly daring. Even if you were to cross this walkway a thousand and one times, you would still feel the same. Your phone doesn’t ring here (there is no signal); the vultures and the sound of falling water are the only things that accompany your footsteps.

As you walk, you are reminded of various stories. That of the sailors who laid the first panels in 1901. That of the workers who toiled with cement so that Alfonso XIII would see that their walkway would be as well-remembered as the monarch himself. That of Andrés who, now aged 83, remembers those cold nights sleeping outside until dawn. That of the children on their way home from school; the women going shopping and the youngsters on their bicycles. And then came the years when there were few memories and a great deal of silence, of danger, until the first workers this century, with sheets of glass and helicopters, started a new chapter. And so it continued until this story came to an end, fulfilling the idea of making this a walkway which is no longer the most dangerous in the world, but is definitely the most spectacular.

The restoration of the Caminito del Rey

From the most dangerous footpath to one which is suitable for everybody

In the 1990s and at the start of the new century, a period when the most accidents occurred at the Caminito del Rey, different administrations came up with the idea of restoring the walkway as a tourist attraction. Since local people had stopped using it as a bridge between one village and another, the cement walkway had seriously deteriorated and there were rockfalls and holes all along it. Finally, and as an emergency measure to avoid any more problems, the entrances from Álora and Ardales were destroyed to stop tourists using the Caminito

A quick look back at the newspapers is enough to show that few projects can ‘boast’ of having been announced for more than two decades without ever becoming reality. Until now. During these 20 years the determination was always there, but the plans could not be carried out, for technical as well as financial reasons.

In 2011 Luis Machuca, the architect for the Málaga provincial government, was commissioned to draw up a viable project. His first concern was a major one: “There was no way this could be done.” Until that moment, all the plans had been based on repeating what already existed: a cement walkway, fixed to the rock wall. There was talk of works costing 18 million euros, but this had to be immediately discounted because of the high cost and technical complications. If there was no way of doing it, Luis Machuca was adamant: “We would have to find an alternative.”

Three years of design and one of construction

What if the walkway couldn’t be repaired? What about building a new one above the old one, using different materials? The technicians came up with the solution: a pathway of planks which would be adapted to the terrain, and railings with a metal grille as a safety system. It was decided to divide the project into sections “so they could be put into place in the same way that was done with the original walkway.”

It was so technically complicated that it took longer to design the project (three years) than to build it (12 months). “It seems incredible, the way they did it then. But still, once the technical and environmental complications were sorted out, things progressed. What was really important was to make something that would last, because of the characteristics of the area,” explains the architect.

Workers suspended in space and a helicopter to carry the materials

The difficult surroundings obliged them to define how they were going to work and tackle the construction. If 114 years ago it was sailors who hung over the gorge to install a primitive wooden walkway (the cement version was not created until the 1920s), today’s solution had to be different. Or maybe not. In fact, it was decided to use the services of companies who specialise in vertical works. A large part of the construction involved workers – climbers and potholers – being suspended in space so they could build the 1.2 kilometres of the walkway above the original one, whose remaining stretches have been preserved. Their work involved putting the wooden panels into place with metallic fixings and adapting them to the morphology of the rock.

Once it had been decided that this would be a hanging structure and that climbers would be used to put the pieces into place, the environmental conditions had to be taken into account such as the wind, rain, loose stones and the mere fact that they would be working outdoors. The sustainability of the infrastructure will be evident in the future, as the Caminito del Rey will undergo constant maintenance. To make this simpler, the creators of the project invented a system so that any piece which breaks can be swiftly repaired. These pieces are combined with others of stainless steel which will last much longer.

Transporting the materials through the difficult access was another aspect that had to be tackled. In some areas this could be done by the workers but in others a helicopter had to be used to carry the materials to where the workers needed them.

The construction of the famous bridge: not as difficult as it seems

The most characteristic feature of the Caminito del Rey is the bridge over the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes gorge, which has now been named ‘Puente de Ignacio Mena’ in memory of a member of the provincial government. Its construction, despite the way it looks at first sight, did not involve any extra risk, say those who were involved in building it. The helicopter unloaded the ready-made sections and a team of climbers put them together more than 100 metres above the ground.

This bridge runs parallel to the previous one and it was used because of the elevated cost of repairing the original (nearly three million euros) and the environmental problems of the debris that would be generated. The new bridge was therefore created for reasons of cost, although Luis Machuca cannot rule out the idea that “with the passing of the years” the one which dates back to 1921 may be restored.

Fernando Arranz, the leader of the climbers, does not consider this to be particularly risky work. “We are accustomed to this type of thing. The worst thing was having to work in bad weather for so much of the time,” he says.

Technology to combat errors in calculation

R+D has played an important role in this project, from the use of drones to a laser pointer to enable distances to be measured with absolute precision. This meant that the materials, the panels as well as the bridge, were cut without any errors in calculation. In fact, all the technicians who worked on the project agree that the greatest difficulty was with the system itself, in other words building a simple piece which could then be cut into sections and transported.

For the construction of the new Caminito del Rey, 4,000 wooden panels of treated red pine were used along the walkway; 1,500 metres of stainless steel wire mesh were put into place, twisted into one metre width. Brackets and supports (stainless steel bars pressed into the wall) were also installed along a stretch upon which 12 climbers and about 20 operatives worked, as well as those responsible for the R+D, the manager and chief of works and, of course, the helicopter pilot.

After one year of works, the Caminito del Rey has reopened with a total investment of 2.7 million euros, a sum which differs greatly from that of previous plans.

The experience

The experience

The time has come to enjoy the Caminito del Rey. Those who have already done so say it is an unforgettable experience. The excitement about its restoration, which has converted a dangerous walkway which was only suitable for the most daring into a safe tourist attraction, has resulted in an avalanche of reservations, because it is essential to book in advance.

he interest in this walkway has not only come from Spain. Travel guides and the international media have also featured the reopening of what until now has been ‘the most dangerous path in the world”. One of these is the popular ‘Lonely Planet’ guide"experiencia imprescindible para 2015",which has described it as ‘an essential experience for 2015’, alongside others such as the Ice Cave in Iceland and the World Observatory in New York, at the World Trade Center. Other international media has also published reports about the restoration.

Before booking

It is essential to register in advance in order to visit the Caminito del Rey. Here, we tell you some things you should know before doing so

The distance and the time it takes

The complete trip along the Caminito del Rey is 7.7 kilometres in length, but it is not all walkway. In fact, 4.8 kilometres are accesses and the remainder (about 2.9 kilometres) is the best-known and most spectacular stretch, which includes the Valle del Hoyo. It takes approximately four or five hours to do the walk, according to the Diputación de Málaga, depending on whether you start from Ardales (the downhill trip) or from Álora (ascending). What is important to remember is that this is not a circular walk, in other words when you get to the end you have to return. It is expected that buses will be laid on for this purpose, although at the time of going to press in March 2015, nothing specific has been organised so far.

Opening hours

The winter timetable is from 10.00 to 14.00h, and in the summer it is 10.00 to 17.00h. It is closed on Mondays. If the wind gusts at more than 35 kilometres an hour, the walkway will be closed for safety reasons. It will also be closed on 1st January, and the 24th, 25th and 31st December.

Cost

The Caminito is to be inaugurated to the public on 28th March 2015. For the first six months, entry is free, although this period may be extended for the first year. The definitive price has not yet been decided.

Age restrictions

Children under the age of eight are prohibited. There is no maximum age limit, but “common sense” is recommended.

Pets

Animals are prohibited.

In groups

Because of the limited amount of space, advance booking is obligatory and 50 people are permitted to enter every half an hour, up to a maximum of 600 a day. This decision has been taken by a monitoring committee which will be responsible for making any changes necessary after seeing how this tourist attraction evolves, so it is possible that entry conditions may vary in forthcoming months.

Decide where to star

As there are two possible entrances (Álora and Ardales), it is essential to indicate your preference when you book. Each day, those who will be walking the Caminito will enter it in groups of 50, whichever starting point they have chosen. Both entrances are good, but if you are going by train the station is at El Chorro so you should indicate that you will be using the Álora entrance.

Physical fitness

The walk is long and there are steps, and you also have to cross a valley between the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes and Gaitanejo. The characteristics of the area make mobility somewhat complicated, so although you do not have to be an athlete to discover this enclave, this is something which should be borne in mind. The trip is not recommended for anyone who is not adequately fit, suffers from vertigo, heart or respiratory problems, or who is undergoing medical treatment at the time of their visit.

What time should I book?

It is best to book a time as early as possible in the day so you can enjoy the whole route. You can take a break in the valley between the two walkways, where there is plenty of space to have a snack and rest.

Making a booking

The Diputación Provincial de Málaga has set up an online reservation platform. Remember, if you don’t register you cannot do the Caminito del Rey.

This is where you can book

After booking: Preparing for the visit

How to get there

If travelling by car, it depends where you are coming from. If you want to reach El Chorro from the north, the best way is to take Antequera as a departure point (A-92). Once there, you have two options. One is longer (nearly an hour) and goes via Campillos (A-384) and then El Chorro; or you can go via Valle de Abdalajís (A-343) and then take the MA-226 as far as the destination. The second route is shorter in terms of kilometres; it takes about 40 minutes, but the roads are in worse condition.

If you are coming from Cádiz province, the best way is to go via Ronda (A-367) and then head for Ardales; there, you take the MA-444. The journey takes about an hour (60 kms).

From Málaga, the road to take is the A-357 in the Campillos direction and then choose either Ardales or Álora (the two options for starting the walk).

If you are thinking of going by train, Adif is planning to lay on more services from 28th March 2015. Details can be found on the Renfe website so you can plan your journey.

What is the walk like?

Although entry has to be at a specific time and from a specific point, this does not mean that the route has to be done in a linear fashion and without stopping. Once visitors have passed the control booth at the start, they can enjoy these kilometres at their leisure and as they see fit.

It is important to stress that if you are doing the whole journey and you want to return to your vehicle, the trip will be 16 kilometres in length, not eight, because you will have to do it one way and then come back. This is important to remember for those who are not accustomed to walking such a distance. The Caminito del Rey will be there for many years to come, so there is no need to walk any more than you are realistically able.

What am I going to find?

In the past few years the Caminito del Rey has grown in people’s imaginations as a dangerous and risky place which is only suitable for the most daring. The poor condition of the previous walkway, combined with a series of accidents, resulted in it being closed some time ago. The new infrastructure has eradicated these dangers.

Despite this, the Caminito del Rey is not a stroll through a garden. The walkways, the hanging bridge 105 metres above the ground and the steep walls will inevitably create a sense of vertigo. Visitors will not be putting their lives at risk (nothing could be further from reality), but they should be aware that it will have an impact on the most impressionable users. That, in fact, is the great attraction of the Caminito del Rey.

Rules you must follow

The provincial government has created a document containing the rules which must be followed when doing the Caminito. Let’s take a look at the most relevant and the most curious:

Don’t forget your ticket

To visit the Caminito del Rey it will be obligatory to have an entry ticket showing the name of the person carrying it, and your DNI or other ID document. In the case of children, the details of the person responsible for them will also be shown. Tickets are personal and cannot be transferred.

Helmets are obligatory

The use of a helmet while doing the walk is obligatory, but you do not have to buy one or bring one from home: a helmet will be provided at the starting point at no additional cost.

You are insured

Every visitor is covered by civil liability insurance for any incident during their visit, as long as that incident is not caused by failure to comply with the regulations or is exclusively the fault of the visitor.

Be punctual

Visitors should arrive at the access area at least 30 minutes before the time on their ticket, so the groups can be organised

Keep to the right

The direction of travel will always be on the right, and this must be strictly adhered to, especially on the walkways. When two people pass each other, they should exercise extreme caution to avoid endangering the one who is on the side where the gorge is.

Free for climbers

People who wish to go climbing can access the Caminito del Rey free of charge if they are on their way to practise this sport. When they arrive at the control booths they should demonstrate that they hold civil liability insurance, and must register and sign to say they accept the regulations.

Be prepared: wear suitable footwear, take water, use sun protection…

The Caminito del Rey has been restored to create a tourist attraction which involves a certain amount of physical effort. For that reason it is advisable to carry water or some other type of energy drink; chocolate, dried fruits or fruit; sun protection cream and a cap, as well as clothing which is suitable for the season in which you are making the trip. Shoes that are suitable for walking are especially important.

No lavatories

It should be remembered that once you have started the walk and until you leave it, there are no bathroom facilities.

Take care with the rocks

As this is an activity which takes place in a mountainous area, there could be small rockfalls.

Carrying someone else is forbidden

You may not pick anyone up in your arms (not even children) along the walkways.

No umbrellas

The use of umbrellas is forbidden when it is raining. The use of rain jackets or similar is, however, obligatory.

Smoking is forbidden

It is forbidden to light any type of fire or to smoke during the walk.

Photos without a tripod

You may not use a tripod to take photos or film anything, nor any other equipment that could block the way. The use of drones or similar equipment is also banned.

No shouting, no echoes

You may not shout or listen to loud music.

No disposal of ashes

It is specifically forbidden to scatter the ashes of deceased loved ones during the trip.

On the way: What you shouldn’t miss when doing the walk

The experience of being on a hanging platform, or one which is fixed to the wall of a gorge many metres above the ground, and the spectacular landscapes are the first things that come to mind when someone talks of the Caminito del Rey. However, once you have started the route, there are some details you should be sure not to miss.

The Ignacio Mena hanging bridge: between vertigo and movement

This impressive hanging bridge, which is named after a late member of the provincial government, is probably the most impressive attraction of the whole route. Situated at the entrance from Álora, this work of engineering measures just over 30 metres in length and, at 105 metres above the ground, it is one of the highest points of the whole walkway. As it is a hanging bridge it moves, and the grid floor allows you to see the water in the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes gorge below. This part of the walk is the one which produces the greatest sensation of vertigo, and that is precisely why it absolutely has to be visited. Several climbers were involved in its construction, putting into place sections which were brought to them from the air by helicopter.

The valley: a path between walkways

The two areas of walkway – Gaitanes and Gaitanejo – are divided in half by a beautiful path which leads through a valley between the waters of El Chorro reservoir. It is approximately three kilometres long and is the ideal spot to stop for a rest, have a snack or even look at the railway lines and watch the trains go by.

Fossils: walls with history

Especially in the area of the walkway which crosses the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes, it is easy to find fossils encrusted in the walls. Millions of years ago, these rock walls were part of the ocean bed.

The old zipwire: a sad story which forms part of the Caminito

A few metres after crossing the hanging bridge – if you are starting from Álora – visitors will find an old rope which hangs down towards the bottom of the gorge. It is all that remains of an old zipwire and was the scene of a tragedy on 11th August 2000. The zipwire ran for about 100 metres, from the old walkway to the start of one of the railway lines. Three young men, Antonio, Andrés and Martín, lost their lives on that day when the part of the rope beside the tunnel came away from the wall and plunged into space. A black plaque which was placed there in their memory by their friends and families serves as a reminder for visitors that although the Caminito is a safe place nowadays, its past contains some dark and emotional chapters. The design of the restoration allowed this rope to be left in place.

A few metres after crossing the hanging bridge – if you are starting from Álora – visitors will find an old rope which hangs down towards the bottom of the gorge. It is all that remains of an old zipwire and was the scene of a tragedy on 11th August 2000. The zipwire ran for about 100 metres, from the old walkway to the start of one of the railway lines. Three young men, Antonio, Andrés and Martín, lost their lives on that day when the part of the rope beside the tunnel came away from the wall and plunged into space. A black plaque which was placed there in their memory by their friends and families serves as a reminder for visitors that although the Caminito is a safe place nowadays, its past contains some dark and emotional chapters. The design of the restoration allowed this rope to be left in place.

A viewing point of glass: a short walk above open air

If you have managed to overcome the vertigo produced by the height of the enclave and the proximity of the cliffs, you can always go one step further and walk over a glass viewing point above open air. As it is transparent, you can clearly see the bottom of the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes gorge. This is one of the most attractive places to take photos.

Although we have selected five key points, the complete visit has many more features on offer, some of which can produce a sense of claustrophobia – such as the cave leading to the entrance – and others which are impressive, such as looking at the old walkway which is full of holes and has been left in its existing condition.

The history of the Caminito del Rey

History

Today it is a tourist route which appears in guides all over the world, but the origins of the Caminito del Rey were somewhat different. It was originally conceived as a service path, and has passed through different stages. In the final years before its closure – when it had already been given the nickname of the ‘most dangerous walkway in the world’ – it was only used by the bravest and most daring. But before that, children would use it to get to school, without anyone to guide them, and couples would hide themselves away between the walls of the gorge; local people would walk along it to see and be seen… and further back still, more than a century ago, there wasn’t even any cement.

A wooden pathway built by sailors

It is curious that the original Caminito was made of wood. The first panels of the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes gorge were put into place in 1901 and this was not done by labourers but by people who were used to living far from terra firma. Those who put that primitive path together were sailors; the original one bore hardly any relation to the new one, as it was tied with ropes from the top of the rock and suspended in space, something to which the sailors were already accustomed on board ship.

But the reason for this path and everything to do with it began years earlier, during the construction of the Córdoba-Málaga railway. It was then that the Loring family, who held the railway concession, realised the potential of the Guadalhorce river and the waterfalls in the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes gorge for generating electricity.

Engineer and businessman Jorge Loring, the first marquis of the House of Loring, also acquired this concession but he did not exploit it. It was another engineer who was related to the family by marriage, Rafael Benjumea Burín, who took over the reins of a project which over time led to him becoming a government minister and gaining the title of Conde de Guadalhorce.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were important changes in the means of generating energy. The steam machines of old were left behind and gave way to central hydroelectric stations. Benjumea saw the potential of El Chorro to generate sufficient energy to supply Malaga and also cover the needs of its industry. His dream was fulfilled in leaps and bounds years later, when it even began to supply electricity to villages in Granada and Almería.

In 1903, the Salto Hidroeléctrico of El Chorro began operating. This small dam elevated the level of the river, and a small channel covered with pipes was created. To control it, Benjumea contracted sailors to build a walkway of panels so the area could be accessed and maintenance works could be carried out. It involved the creation of a parallel platform to control the sluice gate and the accesses to the dam. That was the first stretch of the present Caminito del Rey.

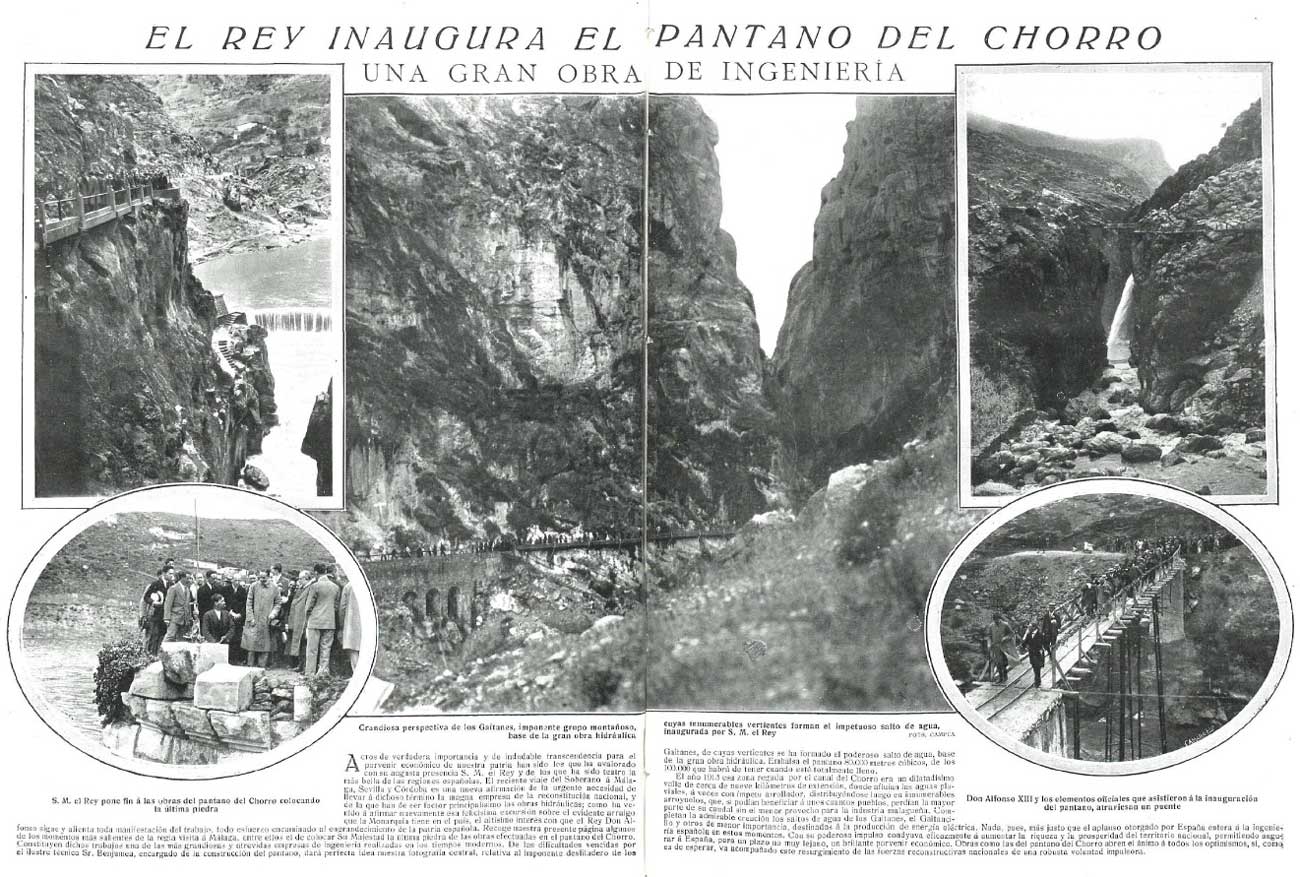

A project to impress a King

In 1903, Benjumea founded the Sociedad Hidroeléctrica del Chorro with the aim of building a large reservoir. Once the project was given approval, it was revised again to include a dam which was 50 metres in height, and a capacity for storing 80 cubic hectometres of water. Despite the shortage of materials as a result of the First World War, the works were completed on 21st May 1921.

Construction work on the El Chorro dam, which was inaugurated in 1921This project was so important that King Alfonso XII came to put the final stone into place. A stone armchair, known today as the King’s Chair, remains to commemorate the monarch’s visit.

Benjumea, as an engineer, saw this precarious walkway of panels as a way to surprise the monarch. While the major project was under way, he decided to take a step further: remove the old structure and change it for one of cement with railway sleepers as a support. “The caminito can be considered a type of publicity stunt by Benjumea for the dam,” explains Isabel Bestué, architect and author of the book 'Salto hidroeléctrico del Chorro. estudio para la restauracion del "caminito del rey'.

At the inauguration, Alfonso XII didn’t cross it all the way, even though the newspapers at the time praised his bravery and talked about the fears of the entourage who were accompanying him. He barely walked one third of it, just enough for it to bear the name ‘Caminito del Rey’, or King’s Pathway, from then onwards.

Magazine La Esfera, 1921A path in daily use: for going to school, shopping, a meeting place…

Andrés Carrasco, who is 83, remembers perfectly what that path used to be like. “I remember it as if it were yesterday,” he says. He was born in El Chorro and for 65 years his goats pastured in the area of the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes gorge, so he crossed the walkway nearly every day. It rapidly became an everyday part of life for the people of El Chorro and other nearby areas.

The area of Gaitanejo, for example, which is where the the water channel of the hydroelectric station starts, was inhabited by several families, some of whom worked on maintenance of the plant, while others were goatherds or farmers. For all of them, the opening of this service path nearly 100 metres above the bottom of the gorge gave them a quick and easy way of getting to El Chorro.

After the dam was built, and later called the Conde de Guadalhorce reservoir, some of the workers settled here permanently. For all of them, the existence of the Caminito del Rey was vital because it was a relatively short way for their children to go to school, it meant that the women could go and buy food and essentials and all the residents could keep in direct contact with other communities further into the mountains.

Andrés, a retired shepherd, recalls that some nights he even slept somewhere along the route. “There was nobody there, just the goats (which he was taking further down), my dogs and me,” he says. When dawn broke and he could hear the children making their way to school, he would get up and continue along his way.,

The Caminito del Rey was really quite busy, by day and by night – it even had electric light. It wasn’t just a means of passage, but also a meeting point. It became an integral part of daily life for the families who lived in the area; it accompanied, and marked, some of the most important moments of their lives.

Abandoned, deteriorated and dangerous

The path was in good condition while it was essential for local people. It even had a guard who was in charge of maintaining it and keeping it clean. As the years passed, though, the path was no longer essential and it was neglected. The passage of time and use by animals resulted in stones falling onto the walkway and causing serious damage, especially in the areas where the cement was at its least thick. In the end, even the railing collapsed.

In many areas the railings were missing and there were holes in the cement. / Image courtesy of the Diputación de Málaga

In many areas the railings were missing and there were holes in the cement. / Image courtesy of the Diputación de MálagaFrom then onwards, the path of the Caminito del Rey became highly dangerous. The holes in the surface and the total absence of some stretches meant that people had to hang onto the rock or make daring jumps over the gaps. Visitors stopped going, leaving it for those who were looking for excitement, especially climbers. And its black reputation began to be forged.

n the mid-1990s and after several fatal accidents, it was decided that the walkway should be definitively closed. Some people in the area claim that the final decision came after the death of a 12 year old girl on 23rd July 1993: Rosa Polo, who was from La Rinconada in Sevilla province. She had gone there on an excursion organised by monitors at the summer camps. It seems, according to the ABC newspaper in Sevilla, that she was the first in the line and she fell through a hole she had not noticed in the walkway.

Because of this incident, more and more people started to demand that it be closed. Not long afterwards, it was decided to destroy the entrances at Ardales and Álora and people were told they would be fined if they tried to access the path. However, nothing stopped the most daring, who made it even more popular by making videos of their dangerous feats.

During its 40 years of history, ‘La Garganta’ hotel complex at the entrance to the Caminito has seen a change in the types of visitor: from local people who took the path through necessity to visitors seeking extreme experiences. Fernando García 'Queco', the owner, says that neither the dangers nor the fines were enough to put people off. “Until not long ago, the visitors who came here were exclusively climbers. It was normal for them to ask how to get onto the path. In the end they used the railway line to do so,” he says.

Cinema: The Caminito of the stars

Frank Sinatra, crossing the Alps to escape from the Nazis in ‘Von Ryan’s Express’ (1965); the dramatic end for the Peruvians who were crossing ‘The bridge of San Luis Rey’ (2004); that scene with Brigitte Bardot, Peter Lorre, Raquel Welch… they are all lies. The Voice didn’t even set foot in central Europe to escape, nor did Kathy Bates or Harvey Keitel go to climb mountains in south America. The scenes were all set far away, but in reality they were filmed close to home, specifically between the gorge and the reservoir of El Chorro, and including the Caminito del Rey which has played so many roles on the big screen, featuring in everything from shootings to pursuits.

Omar Sharif also crossed this Malaga landscape on horseback in a film whose shooting was never documented, ‘The Horsemen’ (1971). Artistic director Ángel Cañizares witnessed it being made; together with John Frankenheimer he worked on this film, in which the Spanish countryside was used to represent Afghanistan. “The part played by Sharif was an Afghan horseman who crossed the mountains to get to Kabul, but it was actually filmed in El Chorro,” says this designer who now lives in Alhaurín de la Torre, and who worked shoulder to shoulder with Gil Parrondo and was part of the team that was awarded an Oscar for ‘Patton’ (1970).

Gil Parrondo is one of the few artistic directors who can say they have returned to El Chorro, because he was also responsible for making the walkway part of a Peruvian setting for the most important scene in ‘The bridge of San Luis Rey’, the last full-length film to have been shot in the area. However, now that the Caminito del Rey has been restored, the provincial government hopes that, as well as visits by tourists, it will be used once again as a film location, as Luis Machuca, the architect and coordinator of the restoration team, who describes the walkway as ‘exceptional’, explains. “Now, you can even film more safely than before, and the truth is that the countryside merits it,” he says, recalling the most famous film to have been shot there, ‘Von Ryan’s Express’, starring Frank Sinatra.

It was while shooting that war film that the actor was involved in an altercation at the Pez Espada hotel in Torremolinos and was detained at Malaga police station, although before this occurred director Mark Robson had been able to film the most important scene, in which Sinatra was guiding prisoners from a concentration camp who were escaping by train to Switzerland with the Nazis on their heels. They also tried to flee on foot along the Caminito del Rey, which played its role on the screen with the precision of a Swiss watch. However, Luis Machuca is reproachful of the producers of the film, “because in the final credits they give thanks to Italy for the locations but forget to mention Malaga,” he says.

Before the Sinatra scandal, actress Brigitte Bardot had also been seen here, although she didn’t walk the Caminito. She filmed ‘The Night Heaven Fell’ (1958) on the Guadalhorce river which runs through La Garganta gorge at El Chorro. The film also starred Stephen Boyd (Mesala in Ben Hur) and a donkey with which she fell in love and named… Chorro. At her hotel in Torremolinos, they wouldn’t let her take the donkey into public areas so the actress decided to take him to her room, much to Boyd’s great surprise, as she admits in her memoirs.

Raquel Welch was also at the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes gorge in the film ‘Fathom’ (1967), but she was in a plane. Actually she wasn’t, because the frames in which you see the crazy 007-style flying style of this actress were shot in the studio with images of El Chorro as a backdrop.

If we are talking about scenes filmed at the Caminito del Rey, the finest sequence is the one in 'Holiday in Spain' (1960), with Peter Lorre and Denholm Elliott hurtling along the stone walkways to escape from a shooting. The opportune train tunnel gave them a breathing space and provided an escape route for this quixotic pair. Almost as if it were a time tunnel from which at any moment Frank Sinatra would appear with a sign saying ‘Swiss border’.

The area

The enclave: geology, orography and climate

The Caminito del Rey runs through a spectacular canyon which has three parts: the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes, the Valle del Hoyo and Gaitanejo. The walls of the canyon reach up to 300 metres at their highest point, contrasting with the narrow width, which in some places measures no more than ten metres.

It is set in the natural beauty spot of the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes and its surrounding area, which includes El Chorro. The area covers approximately 9,000 hectares and is situated at the heart of Málaga province; it incorporates part of the municipalities of Álora, Antequera and Valle de Abdalajís, although most of the Caminito walk is in the municipality of Ardales. The area is almost entirely formed by the Río Guadalhorce river basin and its tributaries, the Río Turón, the Río Guadalteba, the Río de la Venta, the Río del Valle and the Arroyo de Granado.

This area contains two large sections which are of environmental interest. One of them is an area of mountains to the north, with the rocky Sierra de Abdalajís and the Sierra de Huma, while to the west and northeast are the Conde de Guadalhorce, Gaitanejo and Guadalhorce reservoirs. It is characterised by its limestone mountain ranges – with a more rugged orography and the highest reliefs – and areas of sandstone with a gentler relief. The other major area to the south is the Sierra de Aguas, which has more woodland and a different geology, of subvolcanic type, which includes an outcrop of peridotites.

The predominant climate is Mediterranean wetland and, in the mountain areas, continental wetland. Temperatures range from 0 to 38ºC, depending on the time of year.

The geological highlights of this area are the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes, the Pico de El Convento, the Arco Gótico, the Tajo del Estudiante, the Sierra de Huma, the Mesas de Villaverde, Las Pedreras (El Chorro) and the caves of El Chorro.

Fauna and flora

This enclave has shown signs of human presence since Neolithic times, and this is something that conditions the fauna and flora of the area. In the most rugged areas over a large part of the territory, conifers have been planted to control erosion. This has not brought back the native vegetation cover, but it has established a population of Aleppo pines. You can mainly find junipers within the protected area, together with oaks, tamarisks, oleander and reedbeds in the rivers and reservoirs, reforested pines, wild olives, Kermes oaks, gorse, broom, fan palms, rosemary and other shrubs.

Among the vertebrate fauna there are a total of 207 species: 9 types of fish, 7 amphibians, 13 reptiles, 30 mammals and 148 birds, especially birds of prey. It is not difficult to spot vultures and eagles from the Caminito del Rey, while at night the owl is the king of the area. Within the natural beauty spot there are a multitude of species of fauna of great value, either because they are unique, because of their environmental importance or because they are endangered. Among the birds, we have species of special interest such as the common kestrel, the Eurasian eagle owl, barn owl and Griffon vulture. Other birds present in this area are peregrine falcons, Northern goshawks, Bonelli’s eagles and golden eagles, which are classified as ‘almost endangered’. Among the mammals, we find species such as the ibex, which is in a ‘vulnerable’ situation, Eurasian wild cats, genets, the garden dormouse and mongoose.

Traditional uses of the territory

In several places in this area humans have lived in caves, taking advantage of how easy it is to model sandstone. In fact, some of the workers who helped with the construction of the Caminito del Rey even stayed in them. Today only a few caves remain and they are used as storage for agricultural tools. Rural dwellings, many of them built in the 19th century, make up a large part of the development of this area.

Population and land ownership

La evolución de la población ha ido pareja, en un primer momento, al aprovechamiento agrícola y el ganadero y, posteriormente, a la construcción del ferrocarril a finales del siglo XIX. La llegada a la zona del desarrollo eléctrico con la construcción de la presa trajo una nueva oleada de trabajadores. En las décadas de los 60 y 70 del siglo XX se produce un proceso lento pero continuo de abandono de buena parte de la población. Hoy en día existe una escasa población residente en el campo, lo mismo que ocurre con el entorno de los embalses, donde sólo hay contados cortijos importantes.

In terms of land ownership, most of it belongs to private individuals (more than 90 per cent), and the land at the sides of the reservoirs are publicly owned. On the contrary, within the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes beauty spot, 75 per cent is publicly owned (by Town Halls, the Junta de Andalucía, the Agencia Andaluza del Agua and Adif). The trend is for the institutions to buy larger estates, to promote natural and cultural conservation in the area. de mayor tamaño por las administraciones para promover la conservación natural y cultural de la zona.

Bibliographic sources: Javier Blasco Martín, Araceli Cerezo Aguilar, Víctor López Casalengua, Jose Manuel Reus Toré. Ambientura Gaitanes: Un trabajo dirigido y corregido por Félix López Figueroa, catedrático de Ecología de la Universidad de Málaga.

The Caminito del Rey and something more

The Caminito del Rey and something more

In the area round the Caminito del Rey and the natural area of the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes, there are several historic and natural enclaves of great interest. Archaeological sites, the remains of an important Mozarabic settlement and true natural balconies are some of the places which should not be missed by those who want to make the most of a day trip or a weekend getaway in the area.

Day trip: The Caminito del Rey and other suggestions

The Three Reservoirs Viewing Point

There is a natural balcony with views over the three reservoirs which make up this hydrological complex in the Guadalhorce and Guadalteba basin. It is called the ‘Mirador de los Tres Embalses’, from where there are views of the Guadalhorce, Conde de Guadalhorce and Guadalteba reservoirs. This enclave is reached from the road which runs between the reservoirs and Campillos. After leaving your vehicle parked by the information sign, you have to go up some steps to reach this panoramic balcony. Watching the sunset from here is a lovely thing to do.

The Necropolis of Las Aguilillas

Situated close to the road which runs between the reservoirs and Campillos, this consists of seven mortuary structures excavated from the rock. The chambers and numerous niches have been preserved. The funeral items and human remains found here are of great historic value.

Ruins of Bobastro and Mesa de Villaverde

Although no walled area remains, there is no doubt today that Bobastro was a civilian and military bastion for decades. This was the headquarters of general Omar Ben Hafsun, the Muladi who challenged the power of the Umayyads between the final years of the 9th century and the early years of the 10th. Today there is still a great deal to be discovered about this enclave, which is situated in the Mesa de Villaverde. As such, it was impregnable for many years, including during the rule of the Caliphate of Cordoba, which took nearly half a century to control the uprising. In the interior, you can see the remains of a cave church, which together with other findings shows the importance of a rebellion that even created a province within Al-Ándalus. To visit the site, you need to book in advance at the Tourist Office in Ardales.

Viewing Point of theTajo de la Encantada

This natural balcony is very close to the ruins of the town of Bobastro, in the so-called Mesa de Villaverde. It is an ideal place to get a general view of the whole Desfiladero de los Gaitanes area and the Sierra de Huma. You can reach it by vehicle, once you have passed the ruins of Bobastro and the Tajo de la Encantada reservoir. A good camera and a pair of binoculars will be very useful to enjoy more of this enclave.

The chapel of the Virgen de Villaverde and cave houses.

A few metres from the southern mouth of the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes you can see the chapel of the Virgen de Villaverde, which was possibly one of the churches outside the walls of the old Bobastro. In this area there are some important historic remains, such as the caves which for centuries were used as dwellings in this area. Near the chapel, a necropolis from the Mozarabic era was discovered about 50 years ago. There were also remains of a watchtower, known as the Peñón del Moro, which shows the great importance of the area.

The Moorish Starcaise

More than 256 steps form this man-made construction which rises up through the Sierra de Huma, making use of the existing crevices in the rock. Despite its name, it seems that the so-called ‘Moorish’ staircase was built during the past century. Those who climb the steps will come to the Cortijo de Canpedrero estate, from where you can continue on to the top of these mountains. The steps are irregular and have been cut or prepared with stones and rocks to provide an easier way up to the highest area of the mountain range. Climbing the stone staircase has its reward in an incredible panoramic view of the surroundings.

The King’s Chair and the Casa del Conde

Very close to the Parque de Ardales, you can see this stone construction which consists of two benches, a chair and a table. It was here that King Alfonso XIII signed off the completion of the works on the Conde del Guadalhorce reservoir. From the king’s chair, looking across to the shore of the reservoir, you can see the Casa del Ingeniero, or Casa del Conde, one of the most famous picture-postcard scenes of the area.

Tunnel opposite Parque Ardales

Facing the shore of the Guadalhorce reservoir and beside the well-known El Kiosco restaurant, there is an old tunnel which many people use nowadays as a short cut when walking from the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes. It is one of the tunnels which were made for workers who were building the Conde del Guadalhorce reservoir. To go through this passageway, which is about 200 metres long, it is a good idea to take some type of artificial light such as a torch or even a mobile phone. Anyone who has a phobia about dark places is not advised to use this passageway.

The reservoirs

The Desfiladero de los Gaitanes is surrounded and even crossed by three large reservoirs: the Conde de Guadalhorce, Guadalhorce and Guadalteba. You can enjoy tranquil walks beside the reservoirs, or even follow some of the hiking routes. In some places you can practise water sports, such as the area known as Parque Ardales, where there are pedaloes and canoes for hire.

Two-day getaway: To get to know the area better

Ecological reserve of the Turón river

The Turón is the principal river which feeds one of the largest reservoirs in Málaga province, the Conde del Guadalhorce, in the municipality of Ardales. When it converges with the waters of this reservoir, the flow of the river opens up and forms an interesting ecosystem, which nowadays is protected as the Ecological Reserve of El Turón and covers more than 80 hectares. It is a place of ornithological interest, because many wetland birds pass through or nest there such as the little grebe, cormorant, egret, Mallard, Eurasian teal, red-crested pochard, common kestrel and osprey, among others. With regard to vegetation, ashes, oleander, agaves, tamarisks and eucalyptus coexist happily here. There are tracks which run alongside the river, so the surroundings are always attractive.

The Cave of Ardales and Prehistory Information Centre of Guadalteba

This cave contains wall paintings dating back to the Solutrean period (20,000 years B.C.). It is an important Neolithic site (3,800 years B.C.), and there are several burial grounds from the Chalcolithic age (2,700 years B.C.). The cave has been closed to the public for many years and now, due to its importance, it is legally protected and controlled by various sensors, so a balanced system of visits has to be maintained. A guided tour of the cave lasts for approximately three hours. Situated about five kilometres outside the village, this cave was rediscovered in 1821. To visit, you need to book in advance by phoning 952 458 046. The cost of the visit is 8 euros for adults and 5 euros for children.

The Prehistory Information Centre is a museum which offers an educational and general view of the area during that period. You start with an illustrative 15-minute video and then explore the two floors of the building, which contains more than 800 items which help to explain what the Prehistoric Ardales and the Guadalteba region were like.

La Peña Castle

This Moorish fortress crowns the urban centre of Ardales. It was built in the 9th century and was allied to the rebel cause of Bobastro. It was also of great historic importance in the long frontier war between Moors and Christians in the final period of the old Al-Ándalus. There are no visible remains of the original construction; the present towers of the castle are from two different periods, either Nasrid or Christian.

El Turón Castle

Although it is not easy to access nowadays, history lovers should not miss the chance to visit what remains of this Moorish fortress. It was ordered to be built in the 14th century and seized by Christian troops in 1433. Since then it has not been inhabited. Thanks to this, many of its original walls and towers are still standing. This castle used to have about a dozen turrets, which gives an idea of its importance during that period. Below the castle, in the summer, you can swim in the so-called ‘Poza de la Olla’ pool. It is one of the deepest and widest parts of the river, and enables you to enjoy a refreshing bathe while looking up at the Moorish fortress from below.

La Molina Bridge

The first to construct this bridge were the Romans, because one of the roads that linked the countryside with the Mediterranean coast of Andalucía passed through here. The base dates back to the 1st century. With three horseshoe-shaped arches, it is one of the most important works of engineering in the Guadalteba Valley region. It was used to cross the Turón river, which passes below the village of Ardales.

The sulphurous waters of the Carratraca spa

This spa, situated in the historic centre of Carratraca, is fed by sulphurous waters. Its beneficial health properties became especially well-known in the 19th century, when the village was known as Puebla de Baños and was part of Casarabonela. Thanks to these waters, the most influential members of the Málaga bourgeoisie used to visit and made this one of the most sought-after summer places of the era. Nowadays the spa is part of a luxury five-star hotel which manages the use of its waters – which are highly recommended for skin and stomach complaints – in a historic building which is similar to the original one from the 19th century. Since being founded the spa, which is in one of the main streets, has been visited by famous historic personalities such as the Empress Eugenia de Montijo, politician Cánovas del Castillo and Lord Byron.

La Fonda de Pepa

Opposite the spa in Carratraca is one of the most popular venues for local gastronomy, the famous Fonda de Pepa. The restaurant has been operating in the same way for several decades. There is no menu to choose from. You eat what Josefa Romero, better known as Pepa, has prepared that day, which could be anything from a ‘puchero’ soup to tripe stew, a typical ‘gazpachuelo’ from Málaga or a noodle casserole. That is for starters. Among the main courses will be potatoes, eggs and fried chorizo sausage, meatballs in almond sauce, pork cheeks, chicken wings or meat in tomato sauce. In fact, as Josefa says, “eating here is a surprise”. To accompany the food, nothing can beat a red wine with lemonade. Plenty of stories can be told about visitors here, but the most famous was the incognito visit more than 20 years ago by Prince Charles; Pepa had no idea who he was until she read it in the local newspaper several days afterwards.

The Carratraca-Álora road

Although it is due for major improvements, one of the loveliest scenic roads in Málaga province is the one which links the villages of Carratraca and Álora via the Sierra de Aguas. Just over 12 kilometres in length, this winding road not only offers spectacular natural enclaves but is also a reminder of the history of this as a mining area. It also links two villages which are outstanding for their important historical heritage.

The convent of the Virgen de las Flores

On the road between Álora and Carratraca you can visit one of the most important religious buildings in the area, the church of the convent of the Virgen de las Flores, a valuable construction dating back to the 16th century. As well as its architectural merit, it is worth stopping here to enjoy its views over the valley.

Álora Castle

On the road towards the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes from the Guadalhorce Valley you have to pass the town of Álora. There, on a hill beside the town centre, stands its Moorish castle. Its interior, the construction of the Torre de la Vela which was built in the time of the Taifa kingdoms, and a horseshoe arch which is unique in the West, are all worth seeing. Inside, there was also a mosque, over which the present chapel of Santa María de la Encarnación was built. As well as this historical legacy, its location provides a panoramic view over the fertile wetland of the Guadalhorce.

The church of La Encarnación

Another place of interest in the centre of Alora is the church of La Encarnación, which was built in the 17th century. This main church stands in a square in the town centre, which is where the traditional ‘Despedia’ is held in Easter week. It is believed to be the second largest religious building in the whole of Málaga province (only beaten in size by Málaga cathedral). As well as the church, you can visit the Municipal Museum, which bears the name of Rafael Lería and contains an important archaeological and ethnographic collection.

Valle de Abdalajís and its mountains

Very close to the Sierra de Huma is the village of Valle de Abdalajís, which shelters at the foot of the mountain range of the same name. Thanks to this chain of limestone mountains, the municipality sits amid privileged ecological surroundings. Here, you can not only enjoy the views but also practise various adventure sports, including different types of air sport, thanks to the irregular terrain of the area. Valle de Abdalajís also boasts an extensive cultural heritage. One of the most important examples is La Peana, a piece of rock which comes from the famous Arco de los Gigantes of Antequera and which can be seen in the Plaza de San Lorenzo. The emblem of this village also serves as a pedestal, upon which stands a statue with an inscription dedicated to the emperor Trajan.

Walking routes in the area

In the area round the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes and the Caminito del Rey you can follow various walking routes with differing levels of difficulty, ranging from the easy Camino del Gaitanejo to the hard ascent to the peak of Huma.

Sendero de Gaitanejo (dificultad baja)

This is a comfortable circular route of just under 5 kilometres which can be done at an easy pace in about 2 hours. It starts near Parque Ardales, beside the well-known El Kiosco restaurant. You can use the track which starts beside the restaurant or the narrow pedestrian tunnel a few metres away. In either case, you take a woodland track which leads to the hydroelectrical station and the start of the Caminito del Rey. The return trip brings you along the shore of the lake at first, and then goes up to the departure point along a narrow path through a thick pine forest.

Ruta de los embalses (difficulty level: low)

The easiest and shortest route in the area of the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes is the one which starts 50 metres away from La Posada del Conde hotel. From there, you take a path which is barely one kilometre in length, which has to be walked in both directions, on the way and coming back. When it has rained a great deal, you can see different waterfalls from the reservoirs. The vegetation is much more typical of wetland than in other places in the area. There are also slim eucalyptus trees and leafy fig trees.

Sendero Haza del Río (difficulty level: medium)

This track, which starts at the old station building which has now become La Garganta tourist accommodation, leads along the foot of the mountains, where marine fossils from the Jurassic period are still to be found. Although the path does not climb very high, it still offers excellent panoramic views over this valuable geological enclave, including the Desfiladeros de los Gaitanes, the hill on which the ruins of Bobastro stand, the Guadalhorce reservoir and the rocky cliffs of the Haza del Río, where Griffon vultures can often be seen. With regard to vegetation, this alternates between shrubs and undergrowth, such as juniper bushes, broom and fan palms, with woodland trees. The route is barely 5 kilometres long, but it is classified as being of medium difficulty because of the hills.

Ascending to the Huma peak (difficulty level: medium-high)

One of the mountain areas with the best views of the varied landscapes of the Guadalhorce Valley is the Sierra de Huma, a chain of mountains by the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes. Situated between the municipalities of Ardales, Álora and Antequera, this one of the places of greatest ecological beauty in Andalucía, thanks to its limestone features. To discover it in greater detail, you can go up to the top although the climb is particularly difficult for those who are not experienced hikers because it involves several very steep slopes. It is worth doing if you make it to the top, which is 1,181 metres above sea level, because from there you have impressive panoramic views over several regions, including the Guadalhorce and Guadalteba valleys and the Vega de Antequera. It takes at least 3 hours to reach the summit.

Sierra de Huma circular (difficulty level: medium).

Another less difficult way to discover the Sierra de Huma is a circular route which starts practically at the Moorish Staircase. It is about eight kilometres long and goes round the mountain at high levels; there are also some steep slopes. This way, you can enjoy the presence of typical Mediterranean fauna, especially foxes and Ibex, which inhabit the higher areas. Other, more elusive animals include dormice and genets. However, it is the birds of prey which are easiest to spot, such as Griffon vultures, European honey buzzards and golden eagles. The presence of fan palms, which are the only native palm tree of Europe, also adds a unique touch to this walk.

The El Chorro-Ardales route and others on the Great Trail of Málaga

Apart from these itineraries, it should be remembered that stretches of two major hiking routes also pass through this area; one of these is the Great Trail of Málaga, and one part of it links El Chorro with Ardales. The walk involves ascending to the Mesa de Villaverde and therefore runs near the Bobastro ruins, a historical site which is well worth stopping to discover. This route, which is barely 15 kilometres in length, is not very complicated and it allows you to discover some other historical features of the area, such as the Villaverde chapel which was built beside a mediaeval necropolis and the remains of a Mozarabic church. But without a doubt, the principal attraction is what was once the town of Bobastro, which is where historians place the uprising by Omar Ben Hafsun, who challenged the power of the caliphate of Córdoba at the end of the 9th century. His fortress withstood being taken until many years after his death.

Other routes which are part of major itineraries are those which link El Chorro with Campillos via the reservoirs and with the village of Valle de Abdalajís.

What to eat

Plato chorreño

Among the recipes of this area, one of the heartiest is without a doubt the ‘plato chorreño’ which can be tried in restaurants such as the Venta El Pilar. It is a combination of calorific ingredients such as spicy breadcrumbs, chips, fried eggs, black pudding, spicy chorizo sausage and slices of Serrano ham. It is recommended for sharing.

Jabalí al vino tinto

The meat of the wild boar is prepared with great skill beside the Conde del Guadalhorce reservoir. Several restaurants there give it their own special and delicious touch by adding a red wine sauce, which needs to be mopped up with a lot of bread. The texture and flavour of this dish makes it one of the most famous features of local gastronomy.

Sopas perotas

In the area around the reservoirs, Álora has a certain influence and this is something that can be seen by the fact that its most famous dish features on many local menus. The so-called ‘sopa perota’, which is made with locally-grown vegetables and breadcrumbs, includes tomatoes, onions, peppers, fried potatoes, bread, salt and virgin extra olive oil. It can be accompanied by a variety of other ingredients, including sticks of cucumber with salt or olives of the manzanilla aloreña variety.

Migas

This hearty dish of spicy breadcrumbs is prepared by most of the restaurants in the area. Although it is not exclusive to this region, the chefs give it their own special touch, not only in the way it is prepared but also in the amount which is served on the plate.

Revueltos

Set amid such rural surroundings, it is no surprise that the restaurants in the Desfiladero de los Gaitanes area serve different scrambled egg dishes with vegetables including asparagus or tagarnina thistles, or even wild mushrooms (in season).

Porra

When the weather gets hot, the star recipe in this area is the most famous cream of tomato soup in the province of Málaga, the ‘porra’. The influence of Antequera can be noted in the kitchens of restaurants around the lakes, although in this case, like that of the ‘migas’, each establishment gives the soup its own unmistakeable touch.

Roast lamb or Málaga suckling kid.

Although pork tends to dominate the menu of restaurants in the area, there are an increasing number of other options such as lamb and Malaga suckling kid. Both are baked in the oven and served with generous quantities of chips.

Local products

It is becoming more common to see local products on menus, such as the cured meats of Ardales, goats’ cheeses of the Guadalhorce and Guadalteba valleys, manzanilla aloreña olives and wines from places such as Álora, Cártama and Almargen, where they make reds, whites and sweet wines.

Where to eat

In the El Chorro district

La Garganta

Bda. El Chorro s/n, 29552 Álora.

Telf. 952 49 50 00

www.lagarganta.com

Venta El Pilar

Ctra. El Chorro, km. 2 (frente al Desfiladero de los Gaitanes). 29559 Ardales.

Telf: 635 18 95 51

Bar Isabel

Barriada El Chorro s/n. Álora

Telf: 952 49 51 19

Around Parque Ardales

Restaurante El Kiosko

Parque Ardales, s/n. Pantano El Chorro

Telf. 952 11 23 82

www.restauranteelkiosko.com

Restaurante El Mirador

Parque Ardales, zona 4. Pantano El Chorro

Telf. 952 11 98 09 - 629 77 61 07

Restaurante Oasis (Hotel La Posada del Conde)

Parque Ardales, s/n. Junto a la presa del embalse Conde del Guadalhorce

Telf. 952 11 24 11

www.hoteldelconde.com

Bar La Cantina

Parque Ardales, s/n. Junto a la presa del embalse Conde del Guadalhorce

Where to stay

In the El Chorro district

Apartamentos turísticos La Garganta

Bda. El Chorro s/n, 29552 Álora.

Telf. 952 49 50 00

www.lagarganta.com

Pensión Estación El Chorro Isabel

Estación El Chorro, s/n. Álora.

Telf: 952 49 50 04

www.lagarganta.com

Finca Rocabella

Las Angosturas, s/n (El Chorro) - Álora

Telf: 629 78 06 58 - 616 42 69 39

www.fincarocabella.com

Camping Albergue El Chorro

Estación El Chorro, s/n - Álora

Telf: 952 49 52 54

La Almona Chic

Las Casitas de el Chorro - Álora

Telf: 952 11 98 72

Casa Rural La Cascada

Las Angosturas, 96 (El Chorro) - Álora

Telf: 952 11 23 16

In the Parque Ardales area

Hotel La Posada del Conde

Parque Ardales, s/n. Junto a la presa del embalse Conde del Guadalhorce

Telf. 952 11 24 11

www.hoteldelconde.com

Parque Ardales. Camping y apartamentos

A orillas del embalse Conde del Guadalhorce

Telf: 952112401 - 951264924

Multi-adventures companies

Ardalestur

Rutas arqueológicas, geológicas, históricas y botánicas por la zona

Telf. 607 39 21 41

www.ardalestur.es

Indiansport

Turismo activo: Piragüismo, espeleología, senderismo, multiaventura, escalada, rápel, etc

Parque Ardales 29550 Ardales

Telf: 951 21 20 11/ 686 47 92 88

www.indiansport.es

Asociación Montañera de El Chorro

Turismo activo: Escalada y montañismo

Refugio Villa Huma. El Chorro (Álora).

Telf: 652 41 20 55

contact@asociacionmontaneraelchorro.com

Coordination and script: Elena de Miguel

Multimedia coordination: Luis Moret

Web design and development: Juanjo Fernández

Text: Ivan Gelibter, Javier Almellones, Ángel de los Ríos y Francisco Griñán

Video: Pedro J. Quero, Iván Gelibter y Félix Matamala

Pictures: Carlos Moret, Álvaro Cabrera, Iván Gelibter y Ñito Salas

Graphic documentation sources:

Ayuntamiento de Ardales

Diputación de Málaga

Archivo Sevillana-Endesa.

Biblioteca Real de Palacio

Archivo General de la Administración

Foto Colección Pedro Cantalejo Duarte.

Archivo Arenas

No-Do (RTVE)

El Caminito del Rey

Una maravilla a 105 metros del suelo

Spanish version